-

Port Authority

-

Port Authority

Dependent on State Ports, it is the public body in charge of managing one of the 46 Spanish ports of general interest: the port of Alicante.

-

Port Authority

-

Port Community

-

Port Community

A comprehensive vision is essential to improve productivity and connectivity, the Port Community integrates all participants in logistics and business operations

-

Port Community

-

Deal

-

Deal

The port is essential in the logistical gear of the province, and of the state economy. We are always connected to offer you solutions.

-

Deal

-

Sustainable innovation

-

Sustainable innovation

The port is a space for open innovation, learning development, collaborative work and a cooking workshop

-

Sustainable innovation

-

Environment

-

Environment

One of the strategic priorities of the Port Authority is caring for the environment and optimizing port activities focused on sustainability

-

Environment

-

City port

-

City port

Alicante, a seafaring city, has grown through the centuries strengthened by its port. Its climate, the sun, places open to the city, to enjoy them, to walk them, to live them.

-

City port

Brief history

The configuration of the bay of Alicante, lined with many of the winds that whip the coastline and whose sandy bottoms and algae populate the waves of storms, have fostered the establishment of human settlements from very distant times. These indigenous populations took advantage of the shelter of the Alicante roadstead, bordered to the north by Cabo de las Huertas and to the south by Santa Pola, to prosper.

Chronology of history

THE ORIGINS OF THE PORT

TOSSAL OF MANISES

MIDDLE AGES

THE RECONQUEST

KINGDOM ARAGON

MODERN AGE

PORT OF CASTILLA

THE DEVELOPMENT

THE BOARD OF WORKS

WEST SPRINGS

YEARS 60 AND 70

IBERS AND ROMANS Iberians and Romans in the coastal strip of Alicante

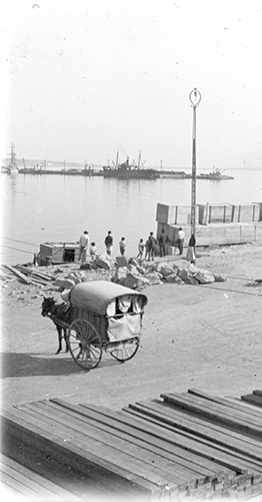

The configuration of the bay of Alicante, lined with many of the winds that whip the coastline and whose sandy bottoms and algae populate the waves of storms, have fostered the establishment of human settlements from very distant times. These indigenous populations took advantage of the shelter of the Alicante roadstead, bordered to the north by Cabo de las Huertas and to the south by Santa Pola, to prosper.

See moreIBERS AND ROMANS Tossal de les Basses (712/1248)

The socio-political context could also determine the abandonment of the Iberian town, because in the context of the II Punic Wars, the Tossal de Manises, located on the opposite bank of the lagoon, was occupied. This military fort had defensive structures of superior resistance, such as walls and towers.

See moreALICANTE IN THE MIDDLE AGES The strategic importance of the port of Alicante in the Middle Ages

The few medieval references that have survived to our time prevent us from venturing an exact date for the beginning of the construction of a pier in Alicante. Despite this lack of documents, the few that are preserved from those remote times always highlight the port and commercial character of the city of Alicante.

See moreRECONQUEST Castile reconquers Alicante

The last sovereign of the Muslim Kingdom of Valencia capitulated to the Aragonese King Jaime I on September 28, 1238, while the conquest of the Plaza de Alicante by the Infante D. Alfonso, later known as the Wise King, occurred in the year Hegira 644, corresponding to 1246 of the Christian calendar. The conquest of Alicante by the Castilian hosts took place thanks to the Treaty of Almizra (1244), which delimited the territorial expansion of the Aragonese crown, whose border was established in Biar and Jijona, and the Castilian, whose Kingdom of Murcia protected the town of Alicante.

See moreMEDITERRANEAN Aragon dominates the Mediterranean

The Castilian domination of Alicante lasted exactly half a century, as the dynastic problems of the Castilian Crown after the death of Alfonso the Wise were taken advantage of by Aragon, which launched itself to conquer the Kingdom of Murcia. Thus, the Aragonese monarch Jaime II raised the senyera after the armed occupation of the castle. It was April 22, 1296 and among the most illustrious victims of that siege is the Castilian mayor, Nicolás Pérez, who died with the sword and keys to the fortress in his hands.

See moreTHE RISE The rise of Alicante in the Modern Age, from a town to a large commercial port city

The town of Alicante reached the status of city in 1490, under the reign of the monarch Fernando el Católico and only two years before the fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada. “The port condition of the medieval town and the wealth generated around its maritime traffic, together with the collaboration provided to the Catholic Monarchs in the course of the war with Granada, were the arguments that raised Alicante to the category of city” , according to the historian Enrique Giménez López.

See moreMEDITERRANEAN Port of Castilla in the Mediterranean

After the decline of Valencia, the reopening of trade with Italy through the Balearic Islands favored the departure of Castilian wool fleeces; in such a way that Alicante once again became the port of Castile in the Mediterranean, since the access to the plateau through the Vinalopó valley was the one that offered the least orographic difficulties.

See moreINFRASTRUCTURE The development of port infrastructure

In the Modern Age the port infrastructure was, in general, very scarce. Thus, the boats anchored in places close to the coast and the goods were shipped and disembarked by barges. In fact, only in places with a solid commercial flow were expensive works carried out to have a stone pier.

See moreBOARD Constitution of the Port Works Board

Due to its poor condition, in 1795 it was proposed that they be made with consular funds; but, in 1803, a first Board of Works of the Port of Alicante was constituted under the presidency of José Sentmenat, which will have the City’s own and Excise flows. It will have to adhere to the plan presented by Manuel Mirallas in 1794 and will start with a liquid budget of 8,109,150 reals of fleece.

See moreWEST New Poniente docks

The need to have piers with greater depth and the consolidation of the settlement of the Alicante industry in the western part of the Port, as well as an order received by a commission that studied the installation of new fishing ports in Spain, were fundamental factors that originated the drafting of the project “New Docks in Poniente and Fishing Dock for Ships”, a project that was approved in 1933. But the civil war paralyzed the execution of these projects and it was not until 1946 when the Engineer D. Pablo Suárez Sánchez launching the file with a modification of the budget. In 1947 the works of this project were awarded, which for different reasons did not finish until 1953.

See moreYEARS 60 AND 70 Years 60 and 70

During the 60s and 70s, different works were carried out in the existing facilities with the aim of adapting them to the new maritime transport systems (Roll-On Roll-Of traffic, Containers, Perishable Products, etc…).

See moreIberians and Romans in the coastal strip of Alicante

The configuration of the bay of Alicante, lined with many of the winds that whip the coastline and whose sandy bottoms and algae populate the waves of storms, have fostered the establishment of human settlements from very distant times. These indigenous populations took advantage of the shelter of the Alicante roadstead, bordered to the north by Cabo de las Huertas and to the south by Santa Pola, to prosper.

In the 5th century BC, where La Albufereta stands today, a large group of Iberian settlers settled. This enclave, known today as the Tossal de les Basses, occupied the top and slopes of a small hill surrounded by a lagoon. Beyond agricultural work, the Iberians developed a solid and advanced ceramic and silver industry, which served as the basis for their commercial relations. As reflected by the archaeologist Pablo Rosser in the book ‘Surcando el tiempo’, published by MARQ, the walled settlement had an authentic “industrial estate”.

To start production, the southern area of Tossal de les Basses had a jetty. This hypothesis is based on the archaeological excavations carried out at the site, which brought to light a wall of around 26 meters in length, with various rooms and annex buildings, whose function could have been storage; as well as several platforms with overhangs, which could have served as piers.

The port structure of the Iberian town is located on the southern limit of the site. At that time, the marine lagoon of La Albufereta went into the interior of the ravine around 250 meters, if the current coast is taken as a reference. It is therefore feasible that it was used as a mooring point for small boats, while the central part of the lagoon had sufficient draft for anchoring larger boats.

The peak period of the Tossal de les Basses extends between the 5th and 4th centuries BC. However, throughout the 3rd century BC the city of Lucentum (Tossal de Manises) is stealing the spotlight. The decline of the settlement could be due to an alluvium in the late-Iberian period (3rd century BC), according to a sedimentological study of the area. This circumstance prevented maritime communication into the ravine, as a sandy shoal was formed and only a small marine redoubt remained next to La Albufereta beach.

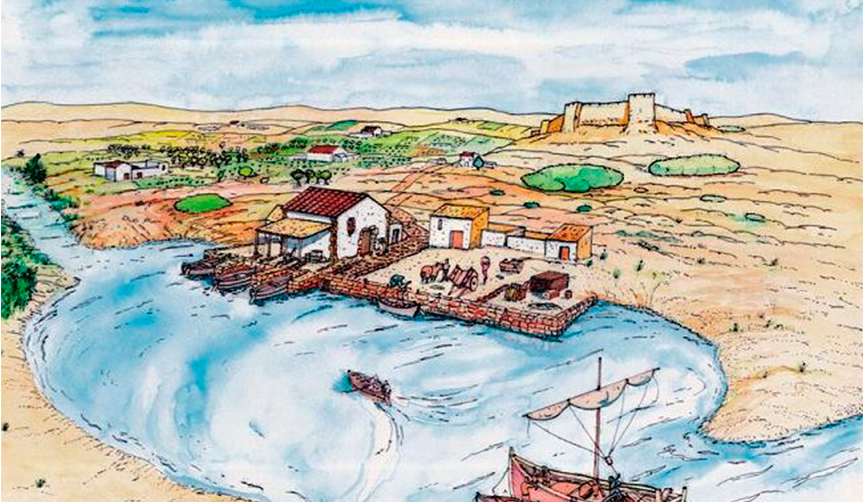

Tossal de les Basses (712/1248)

The socio-political context could also determine the abandonment of the Iberian town, because in the context of the II Punic Wars, the Tossal de Manises, located on the opposite bank of the lagoon, was occupied. This military fort had defensive structures of superior resistance, such as walls and towers.

The presence of the hosts of Carthage (Tunisia) in the Iberian Peninsula, whose southern towns were subdued by Amílcar Barca, made Spain the scene of great battles and sieges. Great Punic leaders such as Hasdrubal and Hannibal, or the Roman saga of the Scipios owe their glory, in part, to what happened in Hispanic lands. But after the defeat of the Carthaginian empire in Zama (201 BC), Rome consolidates its supremacy and power in the Mediterranean.

The city of Tossal de Manises, founded between the IV-III centuries BC. By Iberian population, it lasts until the arrival of Roman domination, which expands the contours outside the fortified Iberian enclosure. At both times, the key element in the development of the settlement will be the existing port on the slopes of the hill.

The Roman port area of La Albufereta had a 48-meter pier, divided into several modules. The excavations carried out have certified the existence of perforations in the top of the wall that were used to tie the boats to them. These primitive piers were located in the northern area of the facility, while in the middle area of the pier there was a drain for the sewage from the enclosure.

The archaeologists, José Ramón Ortega and Marco Aurelio Esquembre, from Arpa Patrimonio, point out in this regard that “small and medium-sized boats would dock in the northern part of the pier, which were moored to this pier by means of holes made in the masonry or in rings iron, also known as norays ”.

Although the maximum draft did not exceed 1.5 meters, in line with this hypothesis, the southern sector would constitute the berthing area for the provision of merchandise and other port tasks. From this dock, wines of renowned prestige, oils, salted fish, cereals and other agricultural resources collected in the different rustic villages located near the city of Lucentum left for larger cities.

The high-imperial Roman port area of Tossal de Manises entered into crisis at the end of the 2nd century AD. and early III A.D. by the extinction of the commercial relations that sustained the economic dynamism of the city and its surroundings. The direct consequence of this decline goes hand in hand with the gradual decline of Rome.

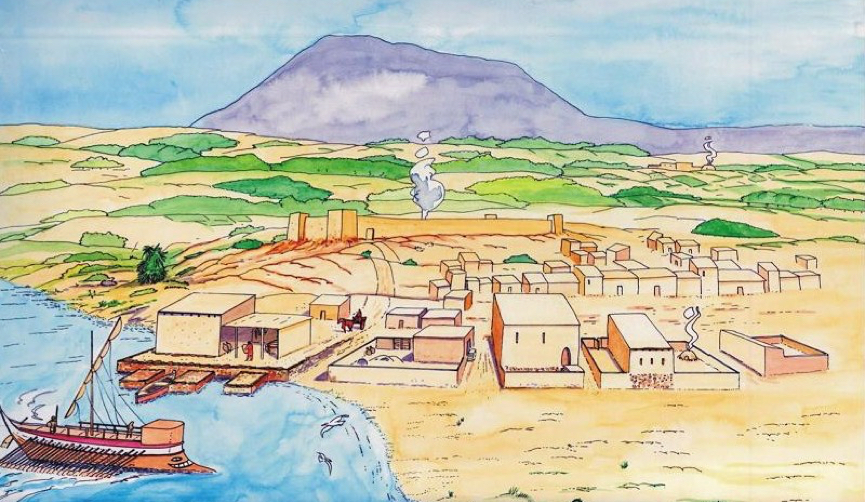

The strategic importance of the port of Alicante in the Middle Ages

The few medieval references that have survived to our time prevent us from venturing an exact date for the beginning of the construction of a pier in Alicante. Despite this lack of documents, the few that are preserved from those remote times always highlight the port and commercial character of the city of Alicante.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the settlement of Tossal de Manises and its port went into decline. Abd Al-Aziz, son of Muza b, will have to arrive. Nusair, governor general of Cairauan, capital of “Ifriqiya” and “Magrib”, in the spring of 713 to seize power from the Visigoth noble Teodomiro and relaunch the maritime trade.

The Muslim village, known as Medina Laqant, has endured in El-Idrisi’s travel writings. This Muslim geographer from the mid-12th century described his time in Alicante as follows: “It is not very important, but it has a large population and good constructions. It has a souk, mosque, aljama and another mosque with preaching. The esparto that grows is exported to all maritime countries. The land bears abundant fruit and vegetables, mainly figs and grapes. It has an unaffordable and well fortified fortress. Despite its minor importance, Alicante is a place where commercial ships and barges are built ”.

The review of this Arab scholar certifies the existence of a jetty, as well as a dry dock and shipyard “where ships are built” for long voyages. According to this hypothesis, raised by various scholars, these industrial port facilities, which already existed in Roman times, could have been on the plateau “dels Antigons” (currently the neighborhoods of Benalúa and Séneca-Autobuses) and the jetty on the Baver beach or Babel.

Castile reconquers Alicante

The last sovereign of the Muslim Kingdom of Valencia capitulated to the Aragonese King Jaime I on September 28, 1238, while the conquest of the Plaza de Alicante by the Infante D. Alfonso, later known as the Wise King, occurred in the year Hegira 644, corresponding to 1246 of the Christian calendar. The conquest of Alicante by the Castilian hosts took place thanks to the Treaty of Almizra (1244), which delimited the territorial expansion of the Aragonese crown, whose border was established in Biar and Jijona, and the Castilian, whose Kingdom of Murcia protected the town of Alicante.

The strategic importance of the port of Alicante for overseas politics did not go unnoticed by Alfonso X el Sabio. In such a way that the Castilian king protected commercial relations with protectionist provisions and tax exemptions. The monarch himself expresses it this way in the city charters: “Of how many ships are armed in the port of Alicant, great and small, and of how many ships are of the time of Alicant, residents or shipowners, that do not give anchorage in the port of Alicant ”.

The privileges concerning facilitating commercial activity were extended a short time later to foreign shipowners, who were also exempted from paying for anchoring (mooring) on ships that docked in the port for their caulking and maintenance in general.

The Wise King decidedly supported the primacy of the port of Alicante and did not hesitate to grant it, together with that of Cartagena, the exclusive embarkation on the Mediterranean coast for all overseas expeditions. Measures of such depth reveal Castile’s interest in promoting by all means the economic development of the port of Alicante, as well as accelerating the repopulation of the town.

Aragon dominates the Mediterranean

The Castilian domination of Alicante lasted exactly half a century, as the dynastic problems of the Castilian Crown after the death of Alfonso the Wise were taken advantage of by Aragon, which launched itself to conquer the Kingdom of Murcia. Thus, the Aragonese monarch Jaime II raised the senyera after the armed occupation of the castle. It was April 22, 1296 and among the most illustrious victims of that siege is the Castilian mayor, Nicolás Pérez, who died with the sword and keys to the fortress in his hands.

The policy of privileges and concessions regarding the port tasks of Alicante by the Crown of Aragon adhered to the line set by the Castilian royal charters. Thus, the solemn royal provision of Jaime II (1308) imposed the fueros of the Kingdom of Valencia but respected those that the town had been enjoying some time ago, in order not to injure any of its legitimately acquired rights.

A new document of the monarch Pedro IV, dated in 1372, delves into the hypothesis of the coexistence of two piers. This document imposes that the introduction of merchandise in Alicante be produced by a single portal, prohibiting unloading on the Baver shore: “… the merchandise is not to be unloaded on the Baver shore but only on the shore that is devant the portal of the sea”.

This royal disposition of Pedro IV to organize the inspection of the products that reached Alicante by sea shows two things, according to the archaeologist Pablo Rosser. On the one hand, the non-existence of any port work in the vicinity of the city of Alicante, since it only speaks of the riverbank; and on the other, the evidence that in the middle of the fourteenth century the bank of the Baver is still being used as an anchorage. However, the chronicler Viravens points out the date of 1248 as the start of the construction of a dock for the disembarkation of goods that extends into the sea 200 feet, having latitude 36.

There will be no written record of the existence of a dock in the city, which would depart from the Puerta del Mar, until the reign of Juan II the Great, one of the longest-lived Aragonese monarchs of the 15th century. In fact, it is already glimpsed in a document from 1433 where the presence of a possible wooden jetty of little length next to the city is revealed.

The confirmation of this indication will be reflected in a second document of this memorable king of Aragon, Navarra, Sardinia and Sicily dated March 18, 1476. In said letter it is ordered that “no part of the anchor flows is applied to the factory of the castle, but that all its collection is used in the conservation and factory of the city dock ”.

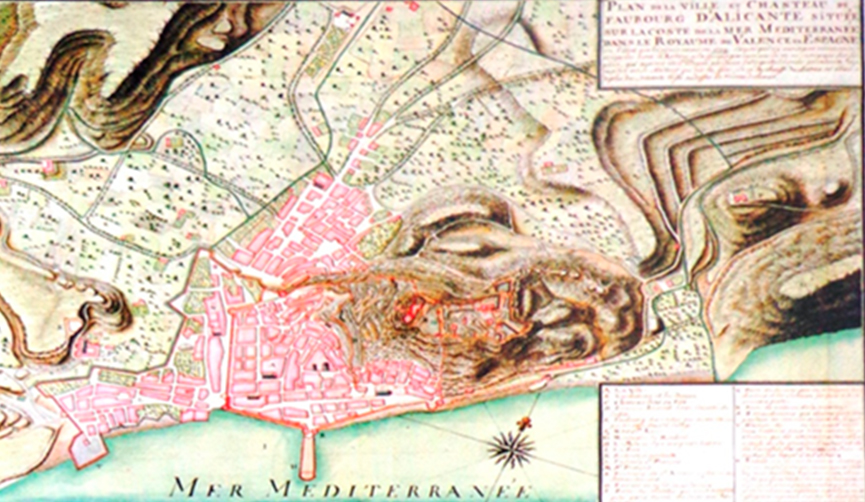

The rise of Alicante in the Modern Age, from a town to a large commercial port city

The town of Alicante reached the status of city in 1490, under the reign of the monarch Fernando el Católico and only two years before the fall of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada. “The port condition of the medieval town and the wealth generated around its maritime traffic, together with the collaboration provided to the Catholic Monarchs in the course of the war with Granada, were the arguments that raised Alicante to the category of city” , according to the historian Enrique Giménez López.

Only two years later, after the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus and the consequent Atlantic expansion, a progressive decline in trade in the Mediterranean Sea began. This circumstance could have relegated the Alicante enclave to a certainly secondary role, especially if one takes into account that the exclusive maritime trade with the “Indies” corresponded to the Castilian Andalusian ports and was banned for the ports belonging to the kingdoms of Spain of the Crown of Aragon.

However, far from diminishing commercial activity, the Alicante port became a flourishing enclave. Guillermina Subirá Jordana points out in his work “Historical Evolution of the Port of Alicante” that the reasons for this boom are due to the conflict of the Germanías, which virulently shook much of the Kingdom of Valencia between 1519 and 1523, as well as its situation on the Levantine coast, which brought him unconditionally closer to the Atlantic trade.

Despite the fact that the port was reduced at the beginning of the 16th century to a masonry dam some 200 steps long by 36 wide, the role played by the port infrastructure in commercial traffic and the security of its walls made Alicante a of the most populated cities on the Levantine coast. In fact, as the chronicler Viciana wrote in 1564, “the 600 houses counted in 1519 increased to 1,100 in 1562”, which together with the suburbs and orchards brought the population closer to 5,000 residents.

Viciana himself in his “Chronicle of Valencia” exposes the reasons for this growth: “The merchants have moved to this city because the pharmacies of their merchandise are very safe within the strong wall and the ships at sea are safe by good footholds. of storm and even of corsairs because with the artillery of the bastions they are cared for and defended by where many Genoese and Milanese merchants have settled ”.

Port of Castilla in the Mediterranean

After the decline of Valencia, the reopening of trade with Italy through the Balearic Islands favored the departure of Castilian wool fleeces; in such a way that Alicante once again became the port of Castile in the Mediterranean, since the access to the plateau through the Vinalopó valley was the one that offered the least orographic difficulties.

In addition to wool bags, soda, salt from the La Mata salt flats, esparto grass, grapes, wine, almonds and table soap were exported from the Alicante enclave, while luxury objects, velvet cloths and table soap were exported from the Italian peninsula. satin, gold webs, silk manufactures, as well as all kinds of weapons.

Salted fish, massively consumed by the lower classes, exceeded in volume any other imported product, except for cereal. Thus, the salting industry was nourished by salted sardines, tuna and cod from the Andalusian and Portuguese Atlantic coast and, even, from 1570 on cod loaded on the island of Newfoundland by English ships.

At the same time, the port became the most important receiver and redistributor of certain goods that arrived thanks to coastal shipping and, from Alicante, were re-exported in Dutch, English or French vessels to Atlantic Europe. Foreign merchants used to participate in this traffic through their agents in the Lucentino municipality.

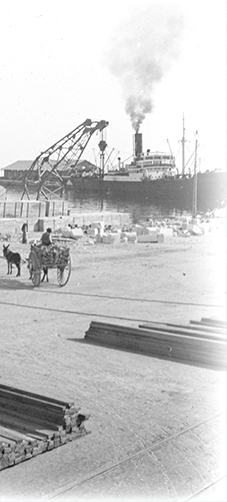

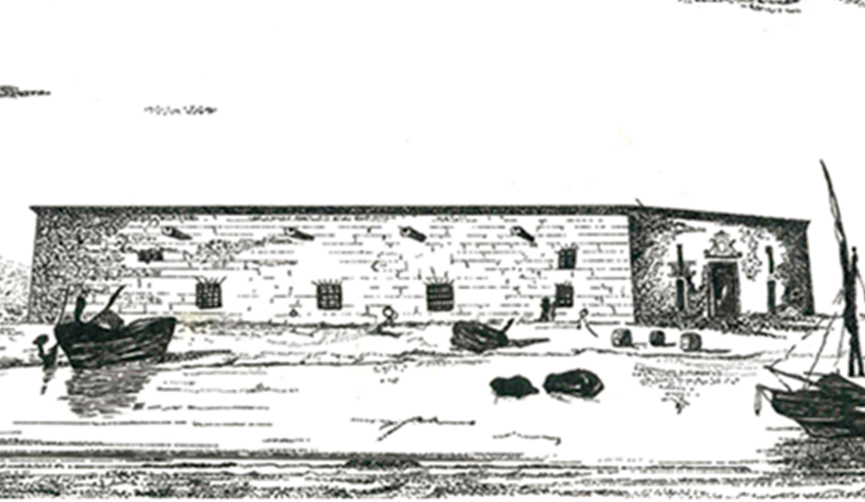

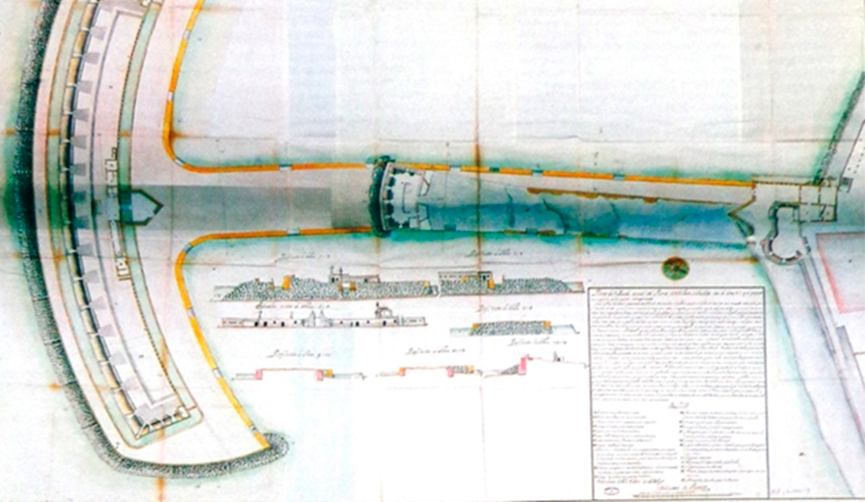

The development of port infrastructure

In the Modern Age the port infrastructure was, in general, very scarce. Thus, the boats anchored in places close to the coast and the goods were shipped and disembarked by barges. In fact, only in places with a solid commercial flow were expensive works carried out to have a stone pier.

The documentary verification of the first shelter breakwater that Alicante had dates from the end of the Middle Ages and did not go deeper than 50 meters into the sea. Warehouses for merchandise and defensive facilities were added to this dock or loader. In fact, in 1491 two bombards were brought from Vizcaya for its defense.

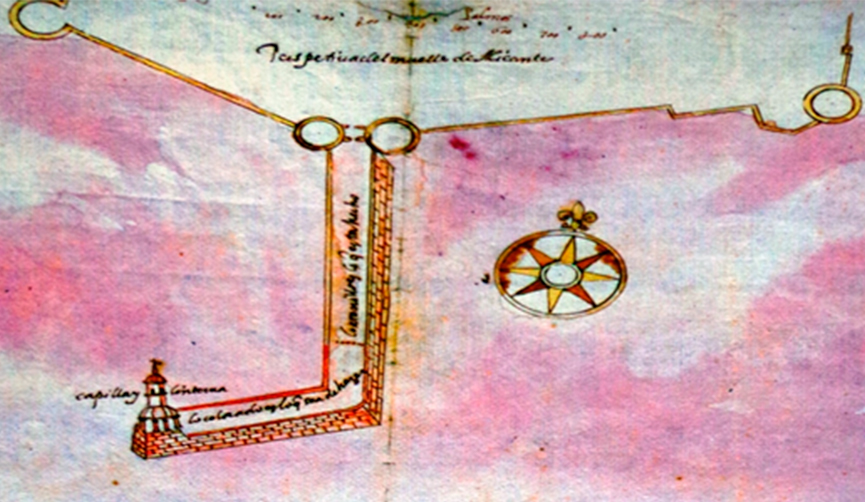

During the 16th century, and with charge to the municipal budgets collected by the right of anchor or dock, slight extensions were made. Despite being destined for the flows that should be used in the works of the dock, references to it disappear until the second half of the century. It will be Felipe II, between 1571 and 1576, who orders the city to continue with the dock factory. The idea that he transmits is to provide shelter for the warships and goods that arrive at the port, and he proposes to build an additional arm or counter-dock at a certain distance from the existing dock, but without specifying it.

In 1575 the order was received to extend the infrastructure from the length already built by about 14 meters, at the same time that the head had to be tilted towards the west to avoid the storm surge. However, the initial project was rectified a year later due to the constant landings produced by the strong avenues coming from the current Rambla de Méndez Núñez and due to the difficulties of docking the galleys. Thus, with respect to the old plan, it was planned to extend it “as long as possible before giving said return.”

The last reference to the port from the 16th century is from 1582, the date on which definitively “the pier was extended by 50 steps to improve its conditions, since it entered the sea”, According to Vicente Bendicho in his work of 1640 “Chronicle of the very Illustrious, Noble and Loyal City of Alicante”, the improvement of the dock was abandoned for a long period of time until in 1688 the final location of the counter-dock was configured, accepting the start-up proposed by the military engineer Pedro Valero. Its cost is estimated at 90,000 ducats.

No feasible novelty contributed to its plant and construction the five projects that the port were made during the 18th century (two in the shape of an inverted L, two in the shape of a hammer, and another that includes the idea of a dock), except for proposing new ideas for the financing of the works.

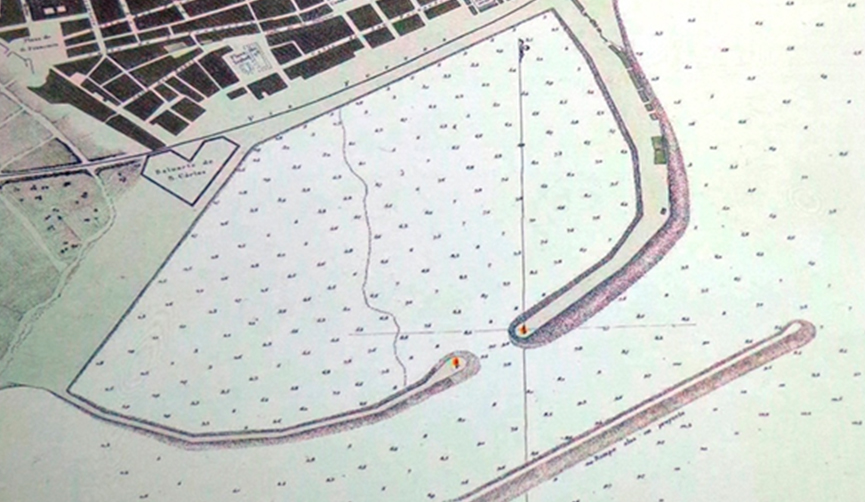

Constitution of the Port Works Board

Due to its poor condition, in 1795 it was proposed that they be made with consular funds; but, in 1803, a first Board of Works of the Port of Alicante was constituted under the presidency of José Sentmenat, which will have the City’s own and Excise flows. It will have to adhere to the plan presented by Manuel Mirallas in 1794 and will start with a liquid budget of 8,109,150 reals of fleece.

At the end of the 19th century, the Port of Alicante was classified as “of General Interest of the First Order” and depended directly on the Ministry of Public Works.

In 1900, local corporations, convinced of the importance of having a Port of General Interest for the city, sent a report to the Ministry requesting the creation of a Port Board with the aim of undertaking expansion reforms that would improve its status. .

The Ministry, in response to this request, authorized the creation of the aforementioned Board of Works, which was definitively constituted on January 11, 1901, and Mr. José Nicolau Sabater was appointed Chief Engineer of the same.

The poor situation of the facilities as well as the urgent need for improvements, led Mr. José Nicolau to establish as a priority a “Project of the Improvement Plan” whose budget amounted to 6,800,000 pesetas and whose main objectives were: the creation a foreport that would offer shelter at the entrance to the Port; and the increase of the linear surface of the existing docks.

This project underwent several modifications over the years, so it was not fully completed until 1911.

Between 1912 and 1917, different works were carried out that consisted mainly in the creation of new piers in the foreport, but the outbreak of the world war caused a delay in the completion of the same, fundamentally motivated by the shortage of raw materials, such as cement. , iron, etc., the project being completed in 1922.

Once the works in the Levante area were completed, the Poniente Sector was improved and expanded with the creation of new piers in the Inner Dock area and the construction of a dry dock. This group of works began to be executed in 1919, ending in 1927.

Between 1928 and 1935, different works were carried out, including the “Extension and Expansion of the Levante Pier” as well as other minor works aimed mainly at improving the existing facilities. It should also be noted that during this period strong investments were made in the acquisition of different materials and machinery.

New Poniente docks

The need to have piers with greater depth and the consolidation of the settlement of the Alicante industry in the western part of the Port, as well as an order received by a commission that studied the installation of new fishing ports in Spain, were fundamental factors that originated the drafting of the project “New Docks in Poniente and Fishing Dock for Ships”, a project that was approved in 1933. But the civil war paralyzed the execution of these projects and it was not until 1946 when the Engineer D. Pablo Suárez Sánchez launching the file with a modification of the budget. In 1947 the works of this project were awarded, which for different reasons did not finish until 1953.

The strong increase that the Port experienced during the decades of the 50s and 60s, in terms of the discharge of petroleum products; the continuous progress made in new technologies for loading and unloading goods, which required larger surfaces in m2, and the appearance of new maritime transport systems, during the 70s, highlighted the deficiency of the docks of Levante and they made it more and more necessary to expand the Port towards the Poniente area.

Years 60 and 70

During the 60s and 70s, different works were carried out in the existing facilities with the aim of adapting them to the new maritime transport systems (Roll-On Roll-Of traffic, Containers, Perishable Products, etc…).

At the beginning of the 80s, and as Director Engineer Mr. Sergio Campos Ferrera began to work on the drafting of the Special Plan for the Port of Alicante, which with an initial investment of 20,000 million pesetas has the following main objectives:

– Improve urban port-city contact.

– Evolve towards a more efficient and profitable commercial port in the Poniente area.

– Reserve the docks in the Levante area for traffic of sports boats, ferries, tourist cruises and warships.